Mere Mortals

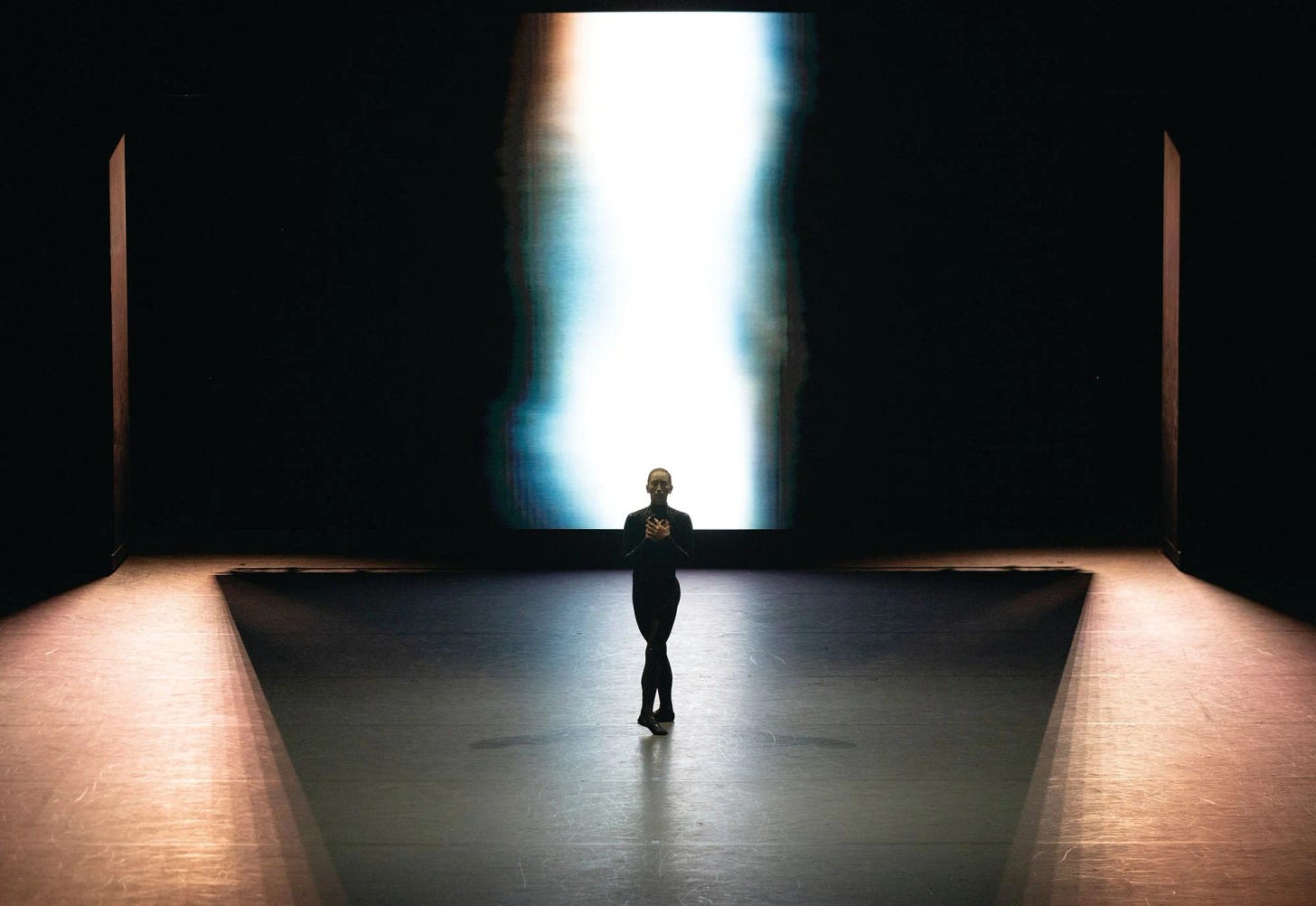

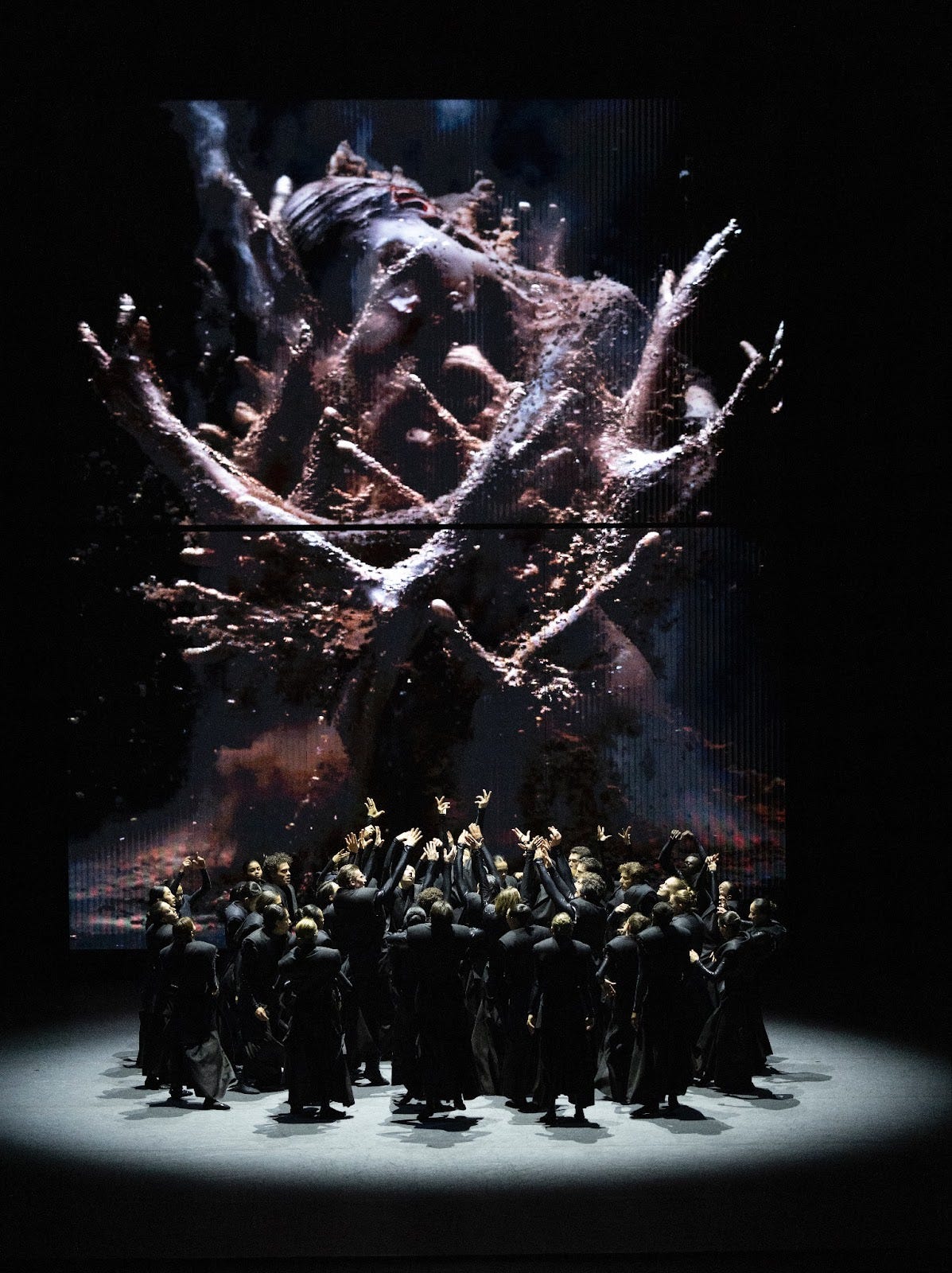

Emerging from a swirl of low bodies, a single dancer rises upwards. Clad in a sinuous black catsuit, at first she is uneasy in her limbs, supported by the hive as she leans and sways. Gaining confidence, she holds her posture, cracking her alien neck and raising one leg in a reptilian stretch. At last she springs into the air, electric and untouchable, scattering the dancers like buckshot and landing in a latex split as the stage pulsates with flashes of bright white light.

Meet Pandora, as played in this performance by principal dancer Jennifer Stahl in the San Francisco Ballet’s stunning world debut production, “Mere Mortals.” The staging is an epic entrance to the city by new creative director Tamara Rojo, a re-interpretation of the Pandora myth for the age of AI. As the myth goes, Prometheus stole fire from Mount Olympus to bring to earth, incensing Zeus. In turn, Zeus and all the gods created Pandora, the first mortal woman, and made her beautiful and gifted. Zeus gives her a jar, along with a caution to never open it. On earth she is sent to Epimetheus, who welcomes her despite all warnings. In her new home, alone with the jar, curiosity gets the better of her and upon opening her vessel, she unleashes all suffering and evil into the world. TLDR of all human history: women are the worst.

This myth first appeared in the ancient Greek writer Hesiod’s creation myth, “Theogony”, where Pandora was described as “a beautiful evil” with no thoughts of her own. Yet Rojo, along with her collaborators, was inspired to tell the story from Pandora’s perspective, presenting her interiority while slyly aligning her with the arrival of artificial intelligence. The character is also gender-expansive, played alternately by male and female dancers.

While the ballet is surely a thematic success, it’s also just an audio-visual marvel. The contemporary influences arrive in a high-speed blender of beauty: Turrell-meets-Rothko rectangles of light frame the stage, a huge corps de ballet marches in Commes des Garçon-ish padded vests, and - could it be? - the viral fist and hip floor pound move from Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion’s infamous “WAP” video. Phew. Ballet is alive and well!

In Rojo’s imagination, Pandora is awakening into her power. She is acquainting herself with the business of being human with total wonderment. I found the most touching part of the performance to be the pas de deux where Pandora meets Epimetheus. While in the original myth he is a fool and she a curse, the creative team compassionately re-imagines this interaction as a mutual discovery. They whisper to each other and breathe together, in a naturally unfolding and raw sensuality. Amidst questioning zylophonic chimes, their bodies glitch and glimmer in matching catsuits with metal fetish zippers up the back, somersaulting in tandem. They are tender and serpentine, their human heads seemingly detached from their slick bodies as they kiss and swell. It made me think about the term Homo Sapiens - “the creatures who think”. I can’t help but imagine this is a human identity that feels outdated while AI races ahead of us at cognition. So then, is this all we have now, our expertise at skin-on-skin? I smelled chlorine and incense, as their chests fibrillated in what can only be described as a simultaneous arachnid orgasm.

In a video released by the ballet, dancer Parker Garrison (Epimetheus) described the pair as having “a curiosity about one another, and together we open the jar.” The woman is not to blame. It is all of us who are curious, who invite strangers in, who open strange jars. We want to know. Myths are mirrors. The way we tell them and re-tell them reveals everything about us. Veteran tech journalist Kara Swisher describes Silicon Valley as a “mirror-tocracy”, ever re-invented in its own self-same, un-diverse image. How we use and design artificial intelligence now says everything about who we are and where we want to go. The liberatory politics and artistic fervor of “Mere Mortals” stands like a challenge to this city that prides itself on innovation. It is a neon beacon planted atop the Opera House, daring us all.

Golden Mammals

For the last few years, I have been studying traditional Indo-Persian painting. To learn, I have been immersed in copying masterworks by the likes of painters Siyah Qalam and Nainsukh. I have come to understand the techniques of this genre, in their alchemical and esoteric glory. We do things like polish the paper and grind stones into paints! Making traditional art is very different than making contemporary art, which is about the ideas over the method. By copying, I am submitting myself to a tradition that is thousands of years old, and my body becomes a tool for re-creating those works in a meditative act of homage. I feel very lucky to have studied in this traditional way. And yet, more recently, I have also felt a desire to realize artwork based on my own ideas using these methods.

As part of that project, I set out to experiment with AI art generation in my work. My first impression of AI artwork was the deluge of cartoon animals and manga-esque avatars that seem to populate the genre. I do not like those aesthetics, to be clear! But I soon realized that the technology is agnostic to style, and the technology itself is incredible.

To make my own piece combining AI and traditional painting, I was inspired by the magical 1960’s cyber-utopian poem “All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace” by Richard Brautigan, a San Francisco poet. The poem is both naive and prescient, as excerpted here:

I like to think (and

the sooner the better!)

of a cybernetic meadow

where mammals and computers

live together in mutually

programming harmony

like pure water

touching clear sky…

and all [are] watched over

by machines of loving grace.

That — or societal collapse. It’s all possible. But why not envision utopias. In an effort to link poetry and design, I sought to recreate this vision in a painting. Using Midjourney, I combined two historical images to come up with new creatures.

The first piece is a page from a Persian manuscript, replete with dragons and swirling botanicals. This painting would have been kept in a muraqqa, like a luxurious scrapbook for a king, with other pasted-in paintings and poems. In Persian the word muraqqa means “that which has been pieced together”, which feels right for the remixing to come. The second piece is a bronze ornament with animals from the Chinese Han Dynasty, my favorite object in the Asian Art Museum in Paris. I simply combined the images with the “blend” command in Midjourney, and then went through dozens of iterations to come up with animals I liked. The final creatures have a circuitry-inlay effect in gold metal. I combined them into a layout on Photoshop, keeping all the strange “terroir” of AI art generation, such as additional limbs and funky renderings of hands. It is what it is.

Finally, I traced the layout onto handmade black Nepalese paper with a porcupine quill, and painted it by hand with real gold paint that I made myself. In art, gold is the color of the divine. The meditative nature of painting in detail by hand can never be underestimated. These creatures are imbued with the movements of my wrist, my body. I wanted to include dragons since they are my favorite metaphor for AI at present. When I hear people whingeing about the laziness of using AI for creative work, I summon the title of the fantastical children’s book, “How to Train Your Dragon”. I am thinking of AI art tools as your personal dragon, readying to take you on a great ride. But you hold the reins, and they require a respect for provenance, a curiosity for combination, and a touch of thoughtful training.

God of the Gasps

What happens when an Evangelical theology-school-drop-out becomes an addict bartender obsessed with quantum physics? The answer, my friends, is the wondrous Megan O’Gieblyn. Now a tech writer, O’Gieblyn attended the kind of hardcore Bible college where Calvinist bros preached against the softness of live-your-best-life Christianity and in favor of “double predestination” by an omnipotent God. In these halls of debate and dogma, O’Gieblyn’s intellect crystallized while her apostasy grew. In leaving the church, she found new idols in the worlds of science and technology, and began to observe how our idolatry of tech writ large mirrors the religious structures she thought she had left behind. Her intricate understandings of theology and cybernetics are interwoven with dark humor in her 2021 treatise, “God Human Animal Machine.” I’ll try to make sense of it here in two parts.

Man vs. Data

In the book O’Gieblyn cites a weathervane of an article written by the editor of Wired Magazine in 2008, declaring that the age of scientific inquiry was dead, killed by big data. Therein he postulated that algorithm had replaced hypothesis, and its findings would always be more powerful. The implications of this reality are both thrilling and sinister. And of course there is a logical linkage here between our blind faith in algorithmic gods and the blind opacity of religious decree. O’Gieblyn quotes the Apostle Paul in saying that God was unknowable, and could only be understood by mortals, “as through a glass darkly”- a line which was perhaps written before the dawn of Windex! But when religion trades in gnostic interpretations of a God so vast as to be unknowable and omnipotent, and dissent is not tolerated… well, this leads to basically all the worst things in human history. So doesn’t it follow that algorithmic faith takes on the quality of blind revelation too? A god you aren’t allowed to question is a terrifying god.

The concept of AI as a black box, making predictions without “showing the work”, has serious implications. When data is always privileged over human experience, human empathy, human nuance… this portends badly. O'Gieblyn gives the most obvious example of predictive policing and sentencing as areas for major concern. While predictive policing is said to reduce personal bias, it is built on institutional biases, reducing people to patterns. While it doesn’t directly use race, gender, and economic status as factors, it uses statistical data that are so closely historically tied to those characteristics as to be inseparable. It looks backwards, not forwards. Through a glass, darkly.

We don’t even understand quantum logic — and yet it is what fuels our technology. Black boxes elude us, even as we build them that way. We are strange gods indeed, but we need not become even stranger to ourselves. Advocating for a humanist counterbalance in the age of AI is not just a song of kumbaya, it is a serious warning lest we build machines that fully dehumanize us. And the guy who is most associated with this line of thinking has to be the tech-Cassandra Jaron Lanier. He literally wrote a book called, “You Are Not a Gadget”.

Lanier is a computer scientist with a simple platform: humans are infinite and data is limited. In a profile in the New Yorker, Lanier is quoted as saying, “I’ve always felt that the human-centered approach to computer science leads to more interesting, more exotic, more wild, and more heroic adventures than the machine-supremacy approach, where information is the highest goal.” His desire to enhance human creativity through tech is admirable, if perhaps quixotic.

The best leaders in any field seek out experts beyond their ken. My fear is that Silicon Valley is so deeply culturally solipsistic that there isn’t even any shame surrounding the lack of a desire to cross-pollinate with other sources of cultural wisdom. One hopes tech leaders would look to leading philosophers and artists to stretch their thinking in this way.

Re-enchantment

O’Gieblyn’s love of tech was first sparked by reading Ray Kurzweil’s 1999 transhumanist text, “The Age of Spiritual Machines.” In it, he predicts the singularity will occur by 2045, when humans will merge with AI or die out. She describes it as “a work of revelation” envisioning a more divine existence for post-human beings. The purported aim of scanning human consciousness is to create a copy that will live beyond the physical body, in a cybernetic version of eternal life. Elon Musk’s company Nueralink has similar goals. Personally, I can’t imagine anything more backwards looking than turning the world into a holographic cemetery of past lives. But maybe I am just one of the dinosaur dissenters who believes the wick of the soul just can’t be digitally preserved.

The quest for soulfulness has driven so many towards divine faith. O’Gieblyn quotes Descartes describing all animals as machines, whereas soul is “something extremely rare and subtle like a wind, a flame.” To have a soul is to be human, so goes the premise. But in our post-Enlightenment fury to seek scientific knowledge, we have been left in an essentially godless, soulless world, exiled from Eden, split from nature. O’Gieblyn wrestles with this dilemma, toying with several possible ways forward. Will it be through finding magic in technology that we can return to enchantment? Will it be through mystery, embracing old rituals and rites in new ways? Will it be through panpsychism, elevating the importance of the natural world and demoting human intelligence vis a vis plant and animal intelligence? Will it be through pure, hard faith, even the faith of mysticism, which delivers certainty in a world of ambiguity?

Where we once sought guidance from gods; now, we just gaze into fancy 4k mirrors, endlessly captivated by our own reflections. What is the job description of a god anyways? Perhaps it should entail weaving new mythologies, crafting sound methods of justice, and yoking technology to wisdom. Who’s to say if we mortals are up to the task. The road ahead is dark, and we will need lanterns of all kinds.